But How It's Done Makes a Big Difference.

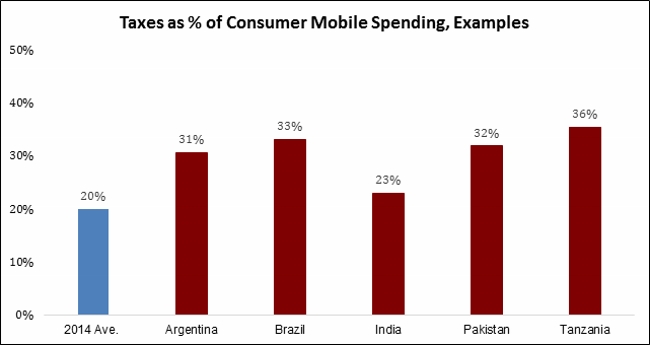

Mobile phones and service are often taxed in the same bracket as caviar, jewelry, alcohol and guns—luxuries and vices. On average, for every dollar spent on mobiles and other ICTs, 33 cents goes to the taxman with 11 cents coming from sector-specific fees. When governments look to fill a budget deficit, as The Economist highlights, it’s all too easy to target the mobile industry, a growing industry and a highly efficient tax collector, especially in countries where there are more ways of avoiding taxes than there are apps.

Should we count the ways taxes and fees are levied? Consumers can face VAT or sales tax, excise duty and a customs fee—the triple play—when they buy a phone, then a fixed fee for activating a new SIM and then VAT and excise duties on services including mobile money. To buy a handset in Gabon consumers pay 18% VAT, a customs duty of 30% and a special telecom tax of $5.00. Once connected, they face an airtime tax of 18%.

Mobile operators face a daunting array of taxes. VAT and customs duties are levied on network equipment, airtime vouchers and SIM cards. Along with taxes on revenue firms also pay tax on profits and are subject to a variety of local municipal taxes. And then come a raft of regulatory fees—for universal service, license and spectrum fees, local and municipal charges, rights of way dues, international gateway license fees, numbering range fees and sometimes, a health insurance tax. Not counting the fees on incoming international calls that many countries still impose. It all adds up, as the chart indicates.

Kalba International, 2017 based on GSMA dataMore than enough taxes? In fact, removing taxes can be a win-win-win for consumers, industry and governments. When Kenya zero-rated mobile handsets in 2009, sales more than doubled and mobile penetration jumped from 50% to 70% in two years. The government collected a third more in taxes in 2011 than it did in the year before zero-rating handsets. Fewer taxes can actually mean more tax revenues for governments and more roads, school benefits, or government jobs for their citizens.

Kalba International, 2017 based on GSMA dataMore than enough taxes? In fact, removing taxes can be a win-win-win for consumers, industry and governments. When Kenya zero-rated mobile handsets in 2009, sales more than doubled and mobile penetration jumped from 50% to 70% in two years. The government collected a third more in taxes in 2011 than it did in the year before zero-rating handsets. Fewer taxes can actually mean more tax revenues for governments and more roads, school benefits, or government jobs for their citizens.

At the same time the growth in mobiles and access to better communications can improve economic growth. For example, World Bank research has shown that a 10% increase in mobile penetration boosts GDP by 0.8%. So what’s the hitch?

The hitch is two-fold. First, re-shaping taxes is always complex. It can involve the Treasury, Finance Ministry, the legislature, the mobile regulator, localities and tax collectors, not even mentioning non-governmental stakeholders. Ensuring the tax code will be re-configured along the right principles—simplicity, transparency, broad applicability—while avoiding regressive burdens on the poor and altering incentives for strong competition is always a challenging task.

The other hitch is the specifics in countries where mobile taxes are being changed. These need to be carefully calibrated. Should the emphasis be on lower taxes on mobiles, on mobile network equipment, or on mobile services? Phone and SIM retailers, including on-the-street kind, may not pay taxes. Import taxes may be difficult to reset unless the country has switched to a working e-customs system; taxing mobile operators less for services, the easiest target, may reduce tax revenues in the short term, upsetting budgets and legislatures, even as it fosters lower prices, higher usage and more economic activity.

So stop, look and listen before you propose a new mobile tax plan in Jordan or Jamaica, Panama or Pakistan. The plan will have a better chance of being accepted, tax revenues will not be disrupted, and the country’s economy will benefit, not just theoretically.

Source: These thoughts were drafted by Gabriel Solomon, Senior Consultant, who until recently served as VP Public Policy at GSMA, where he focused on tax issues in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Send us your Comments or learn about our Regulation & Disputes Practice